“If Mike had been able to seek treatment openly and freely, I think there is a very good chance he would be alive today,” says Leslie McCaddon, widow of US Army Captain Michael R. McCaddon. After almost 20 years of service, Captain McCaddon died by suicide on March 21, 2012. When asked about the reasons leading to his last day, Leslie commented, “the biggest contributing factor was that he was a part of a military culture that stigmatized mental illness and did little to support mental health.”

The stigma tied to mental illness for service members is an over glorified expectation of heroism. We forget that our troops are people, just like us, who can fall ill -- both physically and mentally. Because service members feel that they must live up to these standards, there is a negative attitude tied to seeking support for mental health. They believe it shows weakness— something that does not belong in the military.

This prolonged internal struggle for service members has led to an alarming rise in veteran suicide rates in recent years. It is clear that no one has an answer or solution to this tragic epidemic, otherwise, there wouldn’t be more veteran deaths by suicide than by combat.

How stigma ruins suicide prevention

For veterans, injuries like blown limbs or burns are honored as battle scars and sometimes recognized through awards. Mental illnesses like PTSD, depression and anxiety are not, despite being battle scars nonetheless. It’s harder for others to acknowledge the pain of mental illness when it can’t be seen. Service members often fear the repercussions of seeking help—a loss of respect, a slower career track or being medically retired. They are left feeling isolated, treating their illness as a shameful secret.

These repercussions come from “two opposed agendas so to speak. The services need a trooper, a warrior to go do the nation’s bidding [while] the troop needs to step away and get some help,” explains retired US Army Colonel Angie Holbrook.

It’s not that fellow service members don’t care; the mission doesn’t always allow time for caring. Holbrook states it best: “Leaders are sometimes [stuck] between a rock and a hard place about how much time it takes to let people heal and let people step away from the go, go, go op[eration] tempo.” With time and resources being as limited as they are in the military, it can seem as if those who aren’t cleared for full duty are treated as a last priority.

But the stigma doesn’t begin or end there. It begins with the idea that service members are warriors invincible to the perils of life and ends with feeling isolated, misunderstood, and left behind. As service members transition back to being civilians, they’re ushered to the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) for any mental health care. Unfortunately, the VA has had many problems of their own maintaining facilities able to effectively help veterans long-term.

Current Veteran suicide prevention methods are inadequate

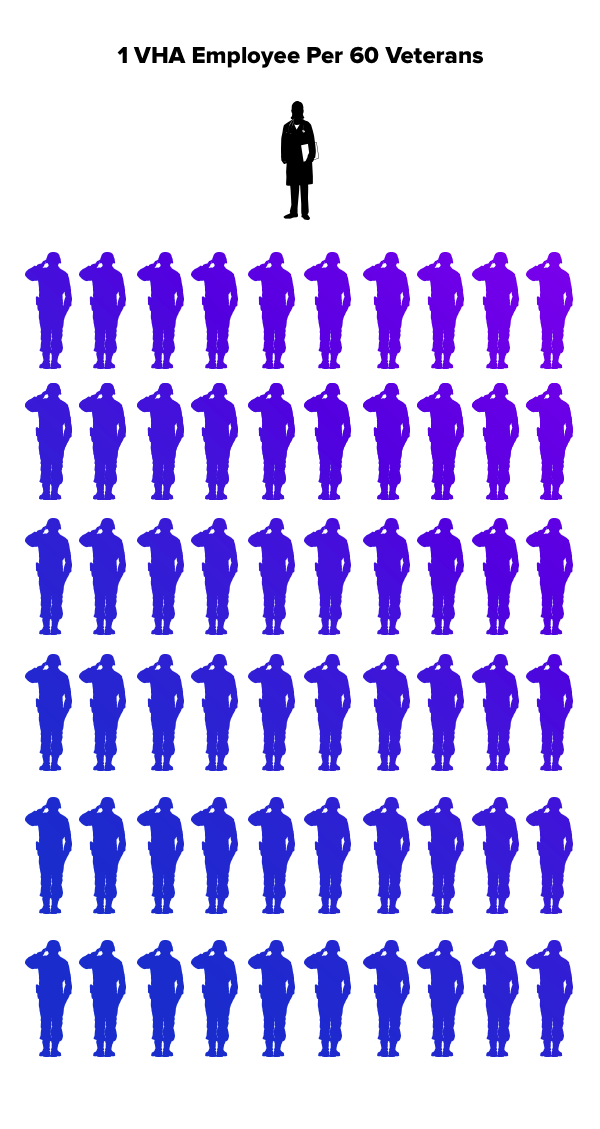

Currently, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has over 40,000 vacancies. In a press release, the VA claims “The best indicators of adequate staffing levels include Veteran access to care and health care outcomes – not vacancies.”

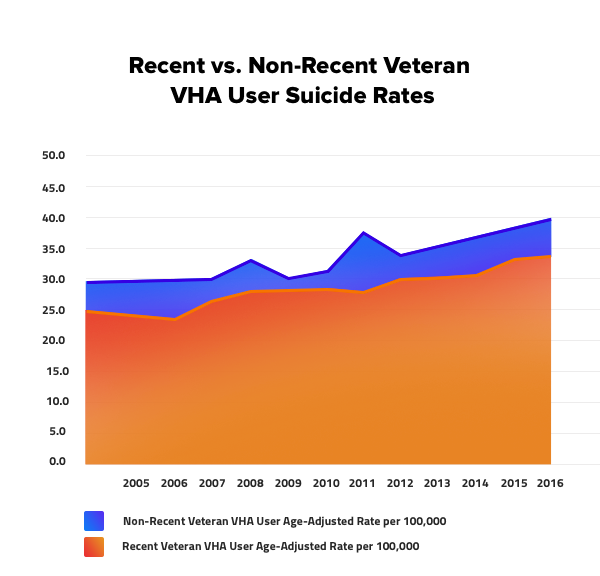

Yet, statistics show “after adjusting for age, the suicide rate among veterans who recently used VHA was higher than among veterans who did not.” And it has been that way since 2005. Having one VHA employee per 60 veterans is not enough considering appointments are sometimes set months apart. VHA employees are left overworked without enough time to see patients frequently, and veterans are left feeling helpless without consistent mental health care.

Even short-term methods such as the Veteran crisis line are met with skepticism. US Navy Veteran Jared Lowell believes crisis relief methods do not work because they are too late, and he knows the person on the other end is supposed to make him feel better in that moment.

In June 2018, the VA issued the “National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide 2018-2028”. The 14 goals and 43 objectives listed within are based on a public health approach to suicide prevention. A large advantage to this approach is the VA acknowledging that suicide prevention will require collaboration from federal, state, and local government entities alongside the media, the workplace, faith-based organizations, educational settings and healthcare organizations. Yet basing the strategy on a public health approach is questionable considering the public’s suicide rates have also been steadily rising.

A major key to Veteran suicide prevention

The existence of the Real Warriors campaign is proof that the Department of Defense (DoD) is aware of the stigma against mental illness in the military. RealWarriors.net is a DoD initiative to encourage help-seeking behavior for the entire military – active duty service members, veterans, and families.

“Having service members talking to [other] service members or veteran[s]…really resonates” states Tech. Sgt Bradley K. Blair, representative of the Real Warriors campaign. That’s why the first step to reducing veteran suicide rates begins with service members.

Service members feel more comfortable speaking with others in the military, because they can relate to the experiences that they have gone through. As Holbrook explains, “when you go to a provider that doesn’t have a sense of understanding our culture as the military, even our vernacular, you spend a lot of time explaining when you’re trying to tell your story or trying to work through things.”

No amount of money or research will reduce the veteran suicide rate if the attitude about mental illnesses in the military does not change. In Leslie’s own words, “Mental health should be supported as routinely as physical health and leadership should be disciplined each and every time they encourage or allow the mistreatment of [a] soldier seeking treatment.”

If you know a military member that is suffering, listen to them and ensure they receive mental health care. There’s nothing wrong with referring them to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (800-273-8255) or the Veterans Crisis Line (use the same number and press “1”). There’s also nothing wrong with listening to them and acknowledging what they feel.

The views expressed are my own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Veteran Affairs, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.