Identity theft starts by associating a name with an address. Local governments can choose whether to make this data available through a simple online search.

We manually researched more than 3,000 local government web sites, and found that 81 percent of counties allow people to search by a homeowner’s name and return their address. In addition, through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to local governments, we found evidence that local governments are selling this information directly to third-parties. For example, Wayne County, MI has received $422,043.48 in revenue by selling this data.

Property tax records allow citizens to compare property assessments so they can ensure they’re not being overcharged on their property tax bill. These records are made public to provide government transparency and accountability, but displaying a property owner’s name with their address is not necessary and can, in fact, harm homeowners.

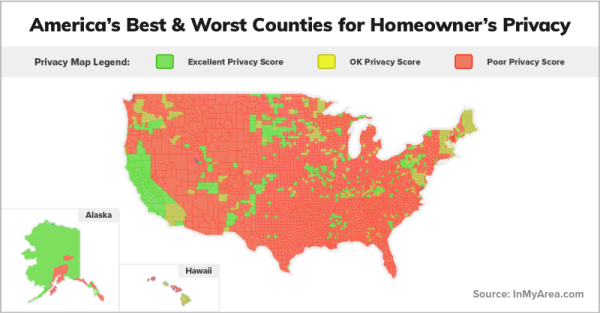

InMyArea.com researchers reviewed property tax records available from all local governments responsible for their maintenance and graded them on their protection of taxpayer personal information. Enter your zip code below to see if your county protects you.

KEY FINDINGS

- 81 percent of counties allow users to search by name and return an address, including counties like Cook County, IL and Miami-Dade County, FL.

- FOIA requests made my InMyArea to X counties showed that this data is sold to third-parties for a total of $XXX.

- California is a leader in personal privacy, 95 percent of counties in the Golden State do not publish name with address.

Public records' flaw endangers personal privacy

Property tax records, classified as public records, are made available by the FOIA. The late Rep. John E. Moss (D-CA) introduced FOIA in 1955. Moss stated, “The present trend toward government secrecy could end in a dictatorship. The more information that is made available, the greater will be the nation’s security.” This may have been true in the pre-internet era, but the ability to remotely access public records raises two questions:

- Why are public records available online when they have the potential to display personally identifiable information (PII)?

- What is the balance between government transparency and personal privacy?

The purpose behind FOIA is to promote government transparency and ensure citizens have undeniable access to public records. In 1996, the Electronic Freedom of Information Act (E-FOIA) amendment required government agencies publish electronic copies of records that are frequently requested. The Privacy Rights Clearinghouse believes, “Making public records accessible to citizens via the Internet is a powerful way to arm people with the tools to keep government accountable.” To ensure citizens’ privacy, E-FOIA allows governments to delete identifying details.

Each state has its own public records that either replicates the federal FOIA or adds further restrictions like California Government Code 6254.21. Per California’s code, the home address, telephone number and other PII of elected or appointed officials cannot be published online. Outside of that, property tax records are typically the responsibility of county tax assessors who decide how they should be displayed online 1 . It is up to the county assessor, or in some states a separate county office, to redact PII, but many fail to do so claiming the law does not allow them to even though E-FOIA does.

Claude Parrish, the Orange County, CA assessor, and his tax collector counterpart, Orange County Treasurer Shari Freidenrich, are a perfect example of an assessor and tax collector that are informed on the issue and seek to protect taxpayers from identity related crimes. People can only search through Orange County’s online property tax records by the property’s address or parcel number - the results will not include the owner’s name. Parrish states, “Hackers and internet thieves like to create new identities using someone with a good credit rating. Homeowners are perfect targets.” Many counties in California, like Sacramento County, cite code 6254.21 as the reason behind withholding name/address online. There are other counties, like Multnomah County, OR, that have a similar policy, but it is not as clear. Oregon Revised Statue (ORS) 192.368 allows individuals to request nondisclosure of records containing their home address, telephone number or email address; however, the individual must provide legal documentation (i.e. a court order or police report) proving their or their family’s safety would be in danger if those pieces of information were made public.

Claude Parrish, Orange County, CA Assessor"

To further protect taxpayers’ privacy, Parrish is now implementing a new process to keep third-parties from collecting citizens’ PII.

Third-party end-users like Zillow purchase property tax records directly from county governments. For example, Wayne County, MI earned over $420,000 between January 2017 and April 2019 just for property tax records. Along with Wayne County, we requested receipts from:

- Broward County, FL – received $76,778 between January 2016 and May 2019

- Allegheny County, PA - received $11,975.35 between April 2016 and April 2019

- San Francisco - received $13,230.88 between January 2018 and May 2019

As lucrative as selling property tax records may be, the real question is what are the third-parties doing with the data? Specifically, the ones that are private. It’s almost obvious what mapping companies/services, real estate and tax collection agencies are using the records for but the consulting firms that offer talent in many specialties, the computer software and IT companies, what are they doing with the data? Even though laws prohibit explicit use of PII without consent, there is no guarantee those companies’ clients are using the records in a way acceptable to who may be affected.

When asking numerous counties why public records are sold, we did not receive a direct answer. Regardless of whether a county displays a name/address online, it is still compromising to sell public records if county officials are not following Parrish’s example. Rather than selling the entire tax roll, Parrish plans to make a copy redacting personal information per request and in accordance with CA code 6254.21. There aren’t any laws forcing Parrish to take these extra steps. He claims it is a personal policy, one that other counties may want to replicate.

There seems to be a misunderstanding of what information counties are required to publish. When asking counties that don’t protect citizens’ PII why an owner’s name is published, the answers boil down to “it’s public record.” E-FOIA states, “To the extent required to prevent a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy, an agency may delete identifying details…” meaning name and address are not meant to be public record. When asked how to remove name/address, we were often told neither can be removed. A few counties, like Bremer County, IA, echo Multnomah County, OR requiring citizens to have a court order to remove PII.

This is the flaw in FOIA. While it may authorize government officials to remove identifying details, it is up to officials to ensure that happens. Taxpayers’ privacy is left in the hands of many who may be less cautious since some states allow public officials to have their own identifying information withheld. The relationship between government transparency and personal privacy is like a seesaw. More government transparency means less personal privacy and vice versa.

As for property records providing accountability, citizens can tell whether they’re being overcharged on their tax bill just by seeing the tax information (i.e. appraisal value and tax rate). Having a property owner’s name published online with their address is unnecessary.

What you can do to protect your personal information

There are few ways people can protect their personal information from property tax records.

A trust is a legal agreement involving a third-party or a trustee, which can be the homeowner, allowing them to manage assets such as property. Putting a property in a trust protects the owner’s information because the name of the trust, which can be anything the owner chooses, will be displayed rather than the owner’s name. Unfortunately, it can cost a couple thousand dollars to set up. Adding more assets to a trust or making it more complex can increase the cost. It is possible to set up a trust without an attorney, but it’d be best to have one for people unfamiliar with how trusts work.

A less expensive way is to get a P.O. Box. Some counties allow property owners to list their P.O. Box as their address rather than having their mailing/property address.

Removing PII from property tax records can be as simple as sending an email requesting redaction or as difficult as formally changing a state’s law. If you live in a county that fails to protect your PII, use the email template below. It is up to citizens to protect their privacy.